Internal Migration: A Cornerstone of China’s Economic Model

In China, 177 million workers live in places other than the area registered in their hukou, China’s “internal passport”. These migrant workers are employed in flexible, low-skilled jobs and have limited access to healthcare, pensions and public education. This situation boosts the competitiveness of China’s growth model, but breeds inequality and slows human capital accumulation.

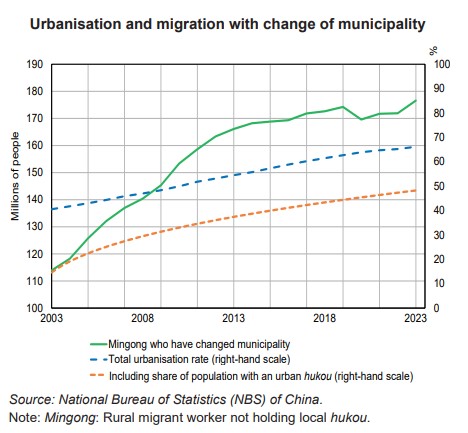

Since 1978, hundreds of millions of people in China have migrated from the countryside to cities, mainly in the east, fuelling the country’s remarkable industrial transition from an economy previously dominated by agriculture (see Chart). In 2023, 66% of the population lived in urban areas.

Rural-urban migration has been driven by a gradual easing of the hukou, a household registration system for Chinese citizens based on their place of origin and their status (agricultural or non-agricultural, or rural or urban). The hukou is often compared to an “internal passport”. Dating back to the Mao era, it was introduced to control population flows and encourage migration to areas needing workers, while preventing slums from forming on the outskirts of large cities.

The rapid growth of internal migration has bolstered the working-age population without a hukou corresponding to their actual situation (177 million people, or 22% of the working-age population). While internal migration is now allowed, migrant workers from rural areas seldom obtain hukou from the city in which they reside or access the entitlements that come with an urban hukou. Migrant workers also work mainly in flexible, low-skilled jobs paid at a lower rate than workers with an urban hukou. Migrant labour is cheap for employers who pay virtually no social security contributions for migrant workers. China’s two-tier labour market thereby contributes to wage moderation, maintaining China’s cost competitiveness.

Living in a city without an urban hukou restricts access to property ownership, although restrictions have been relaxed in recent years in response to the real estate crisis. More importantly, migrant workers are not eligible for healthcare, education or government pensions in the same way as other workers. Migrant workers therefore save at higher rates than the rest of the population and human capital accumulation is slower at the aggregate level.

There has been much talk of reforming the hukou system and restrictions have been eased gradually, mainly in small- and medium-sized cities which attract fewer migrant workers.