Japanification: a Risk for China’s Economy?

China’s decline in growth is characterised by growing imbalances between the prioritisation of industry and investment on one hand and low consumption and the property crisis on the other. While this situation is reminiscent of 1990s Japan, which suffered a weak growth rate and low inflation, China’s economic slowdown could be less severe if its growth model is rebalanced.

The “Japanification” of a country alludes to Japan’s economic situation starting from the early 1990s following decades of rapid growth. It is characterised by weak growth and inflation rates, and extremely low interest rates.

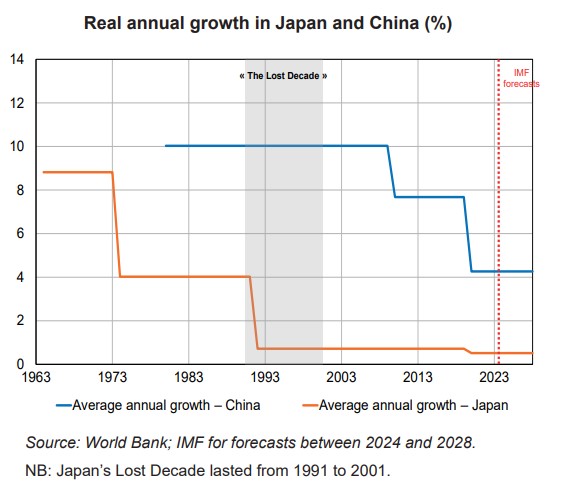

China currently bears many similarities to early-1990s Japan – its growth model is centred on industry and investment, and is reliant on buoyant exports. China is also laden with debt, and suffers from a population decline, a downward trend in growth (see Chart) and inflation, as well as a property sector crisis since 2021.

However, the extent of the decline in growth may be less considerable than in Japan given some of the Chinese economy’s strengths and its ability to learn from Japan’s difficulties. While China has reached the technological frontier in an increasing number of sectors, it is also looking to switch to a new growth model more focused on new technologies and on ramping up productivity.

The implementation of this new model could be hindered by China’s debt-laden local governments, and more generally there are lingering doubts over this model’s ability to sustain high levels of growth.

A similar fate to that suffered by Japan would mean a severe slowdown in the catch-up process, but not necessarily smaller productivity gains than in other countries: when adjusted for demographics, Japan’s growth had been indeed similar to that of other major advanced countries since 1990.