The Dual Income Tax System in Sweden

Sweden was the first country to adopt a dual income tax system, with the progressive taxation of earned income and the flat-rate tax for capital income, under the 1991 tax reform. This reform, which set out to lower taxes and broaden tax bases, has had a positive long-term impact on business investment and labour supply. It was then followed by a significant cut in aggregate tax and social security contributions over time

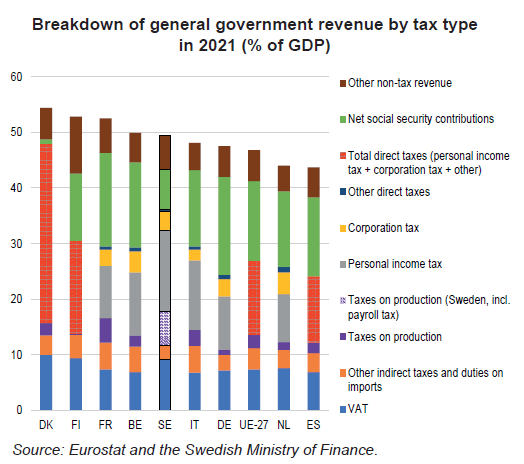

For quite some time Sweden has stood out for its high level of aggregate tax and social security contributions, but over the past twenty years the tax burden has significantly lightened. Households are the hardest hit by the Swedish taxation system. Most general government revenue is generated by indirect taxation and personal income tax, with the latter financing local authorities to a large degree and its marginal rate exceeding 50% in the higher brackets. Tax on personal assets is low.

Most notably, Sweden was the first country to introduce a dual income tax system, with the progressive taxation of labour income and the flat-rate tax for capital income, as part of a major reform in 1991. With a view to bolstering competitiveness, there has also been a constant effort to cut rates and broaden the tax base. The corporation tax rate has been gradually lowered to 20.6%, matching the EU average.

The moderate level of social security contributions is partly attributable to the pension system’s strong reliance on capitalisation. Generally speaking, taxation of the labour factor nevertheless remains relatively high as a result of the general payroll tax.

The 1991 reform resulted in a foreign direct investment boom and a pick-up in the pace of total factor productivity growth. Over the long term, Sweden has one of the highest business investment rates in the EU, but taxation of the labour factor is accompanied by structurally high unemployment.