China’s Dependence on the Property Sector as an Engine of Growth

After twenty years of dazzling development, the Chinese property sector is facing a major crisis. However, beyond its cyclical aspects, this crisis reflects a loss of steam in the Chinese growth model, which is based on a profoundly unbalanced property sector. The authorities are now faced with a dilemma, between the two imponderables of the structural clean-up of the sector and the cyclical recovery of the economy.

The property boom has been a key driver of China’s “economic miracle”. The property sector can be defined as all the economic activities related to real estate, including the management and use of land and buildings by property developers, construction companies and real estate agencies. Property has been a pillar of rapid urbanisation, growth and employment in China since the 1980s. Real estate investment has also been used as a policy tool to stabilise China’s economy. If the economy starts to overheat, monetary policy is tightened and restrictions are placed on buyers and developers. In times of economic slowdown, authorities use bank lending policies to stimulate the property sector, and the economy at large.

China’s growth model is now coming under pressure from evolving demographics, higher prices and rising debt for both households and property developers. The model is also having a negative impact on productivity, wealth distribution and regional equality. Handling this downturn and rebalancing the economic model are serious challenges for China. Depending on estimates, the property sector accounts for between 14% and 30% of China’s GDP. The top of this range is above the level reached in the United States before the 2008 global financial crisis.

In 2020, the Chinese government attempted to tighten regulation in the property sector, putting the most vulnerable developers under financial strain. The result was a sharp contraction in real estate investment, sales and prices, with some developers facing a cash-flow crunch. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) were then forced to intervene and restructure some of the developers.

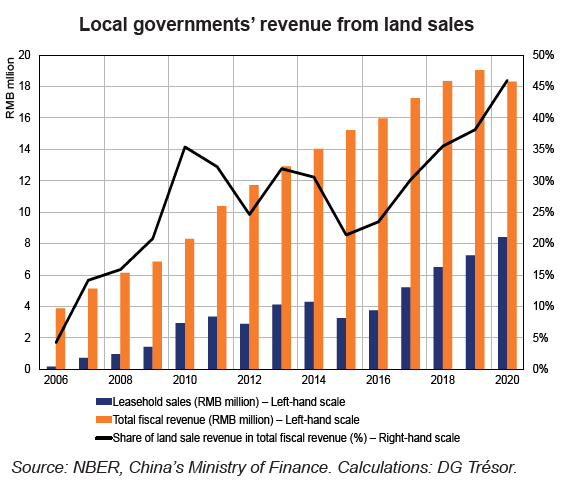

Amid slower growth, largely due to China’s zero-Covid policy and the real estate slump, authorities started to ease some of the restrictions in the property sector in late 2021 – following similar patterns of other property market cycles in the past. These measures have not managed to contain the crisis and are expected to be extended over the course of 2022 and 2023. The sector’s structural problems are likely to persist in coming years, affecting government revenue from the property sector and property developers’ business model. Local government finances are particularly reliant on proceeds from land use rights (see chart opposite).