Trésor-Economics No. 129 - Unionisation in France: paradoxes, challenges and outlook

France is unusual in that it has one of the lowest rates of union membership in the OECD (8% in 2010) with one of the highest rates of collective bargaining coverage (93% in 2008). This paradox points up the particularity of the French model of industrial relations, where the collective bargaining extension procedure means that unions and employer associations negotiate for all sector workers rather than just their own members.

Low union density in France is due to a number of factors: (i) the unions' weight in collective bargaining does not depend on how many members they have, but on their workplace election results; (ii) union membership does not give workers many rights and benefits compared with a good number of our European neighbours; and (iii) the unions are not funded mainly by member dues, but essentially by government, employers and labour-management organisations.

However, France's low union density doesn't leave workers without union representation. Despite low union membership, French unions are firmly established in the workplace and are capable of rallying strong labour support on certain subjects.

Yet this situation could potentially undermine the development of labour-employer relations, whose quality is important to French economic health. In particular, unions have few jobseekers among their members and more permanent workers than staff on flexible employment contracts (essentially temporary employment and fixed-term contracts) in the low-skilled categories (manual and non-manual employees). This can skew their positions on certain issues relating to these categories.

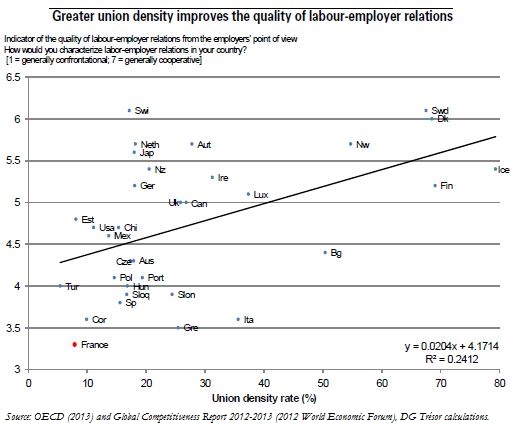

Industrial relations in countries with the highest rates of union density generally run smoothly and are more conducive to negotiation, especially when it comes to structural reforms.

France could do well to consider and test incentives modelled on foreign approaches tailored to the historical and cultural particularities of the French union movement. This could encourage a French style of service model unionism: the unions might be prompted to develop their range of services for their members, as some have already moved to do.

For example, the vocational training reform, with the launch of the personal training account, could give France the opportunity to formalise the role of the unions in providing advice and guidance on the vocational training needed to secure career paths.

Building on recent measures to improve the system of social democracy, thinking needs to be taken forward on how to simplify and clarify union funding.