Trésor-Economics No. 78 - The employment content of growth in the current U.S. recovery

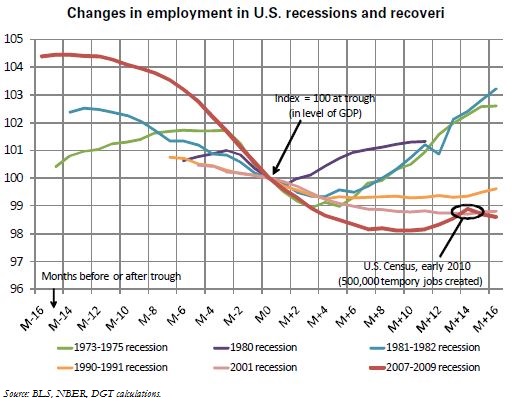

The National Bureau of Economic Research has dated the end of America's "Great Recession" to June 2009, but the very nature of the current U.S. recovery remains uncertain. Growth is fragile; the situation on the labor market remains poor; and any improvement will depend on the strength of economic activity and the job content of the recovery. Historically, throughout the post-war period until the 1980s, a pickup in economic activity was followed by a strong rebound in the labor market; but the periods following the 1990 and 2001 recessions were especially weak in terms of job growth, raising the hypothesis of a long-term shift in the labor market's response to changes in economic activity.

The 2008-2009 recession differs from the previous two recessions by the extent of job losses; this argues for a strong rebound in the labor market during the subsequent recovery. An econometric analysis, however, seems to confirm the hypothesis of a structural shift in the response of employment to changes in GDP, as the current period look like previous "jobless" recoveries more than "classical" recoveries.

The low level of hiring, even after job destructions ended-a characteristic of the post-1990 and 2001 recession recoveries-appears to confirm this diagnosis. The first explanation is the sharp decline in hours worked and the rise in involuntary part-time work during the recession, even if those factors are not specific to the current episode; companies can have their existing employees work more before hiring additional workers.

More fundamentally, weak job creations-to date and in the future-during a recovery appear to be linked to structural changes in the U.S. economy, which reduce the response of employment to GDP growth. A breakdown of employment trends by sector shows that every U.S. recession since 1945 has registered an acceleration in the decline in the share of manufacturing employment in total employment, notably due to high productivity in the manufacturing sector and the outsourcing of certain activities. This gradual deindustrialization has left the services sector-which has a slower response to changes in GDP-as the main source of job creation during recoveries.

Other factors specific to the current recession/recovery are probably also at work, e.g., especially strong uncertainty regarding the economic outlook and the magnitude of the housing crisis which, in addition to the job destructions it entails, also tends to reduce workers' mobility and thus aggravates the problem of matching worker skills to job vacancies.