Trésor-Economics No. 165 - Initial and continuing education: the implications for a knowledge-based economy

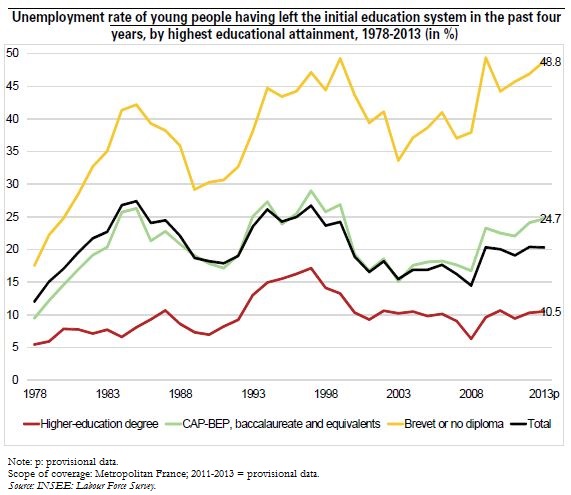

Initial and continuing education play a decisive role in helping people to access the labour market by reducing unemployment risk and duration, and enabling them to obtain higher wages. In France, as in the other OECD countries, the rise in wage earnings procured by a higher-education degree greatly exceeds the cost of obtaining the degree (rate of return: 11.4%). Beyond the personal level, education contributes to increasing productivity, stimulates innovation and technical progress, tends to reduce passive social spending and allows fuller integration into society. These positive effects on the economy and society justify public participation in education funding.

Continuing education does not easily replace initial education. Beyond the acquisition of a diploma, initial education is part of a cumulative, life-long learning process: each learning period is an essential step towards future learning periods. There are two consequences to this. First, primary education is crucial, for skills deficiencies are hard to compensate later. Second, initial education facilitates access to continuing education and makes it more efficient. As a result, the main group to access continuing education today consists of employees, particularly the highest-skilled. Continuing education also benefits employer firms through productivity gains.

According to the OECD 2012 PISA survey, the performance of French 15-year-olds lies within the developed countries' average, but France's ranking has declined since 2000. Moreover, adult numeracy and literacy skills–as measured by the PIAAC survey–seem relatively weak in France by comparison with other OECD countries, but the education level is improving more visibly than in the other countries for the younger cohorts, owing to the rise in the number of secondary- and higher-education graduates.

In 2014, approximately 44% of a birth cohort completed higher education in France, compared with the European Union average of 38%. France aims to raise that proportion to 60% by 2025. To this end, the number of graduates may be expanded by measures to promote an increase in students' success rate, which is currently low for holders of "technological" and vocational baccalaureates in first-cycle university education. Their success could be eased by intensifying support programmes and guidance, and by a better adjustment of education programmes to student profiles.

Raising the number of graduates also requires improving the skills of higher-education entrants. Indeed, high-quality primary and secondary education is essential to pursuing and completing higher-education studies.