How to stimulate consumption

Travelling the last few miles

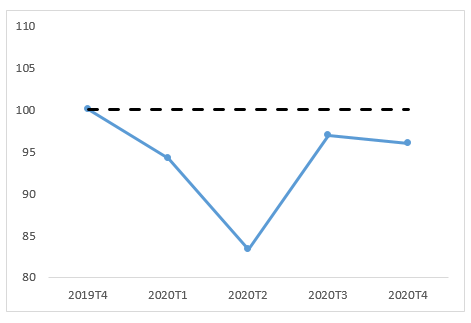

Published on October 6, the latest Insee Conjoncture in France confirms the rapid rebound in household consumption over the summer, the consumption level in Q3 being "only" 3% below pre-crisis level. Since September, though, new health restrictions have interrupted the recovery in sectors that had not yet caught up (hotels and restaurants, transport, leisure), while the catching-up effects are fading for the consumption of durable goods.

Figure 1. Household consumption forecast (Insee)

(100 in 2019 Q4)

Source : Insee, Octobre 6 2020.

This recent development is consistent with the Government's forecast which also takes into account a decline in consumption at the end of 2020 (see post from September 22nd, Growth at the end of the tunnel). The question therefore is how to find the best way to "cover the last few miles" to bring consumption back to its pre-crisis level, at least in those sectors not subject to administrative constraints.

Consumption support can be achieved through two channels:

- Income support, particularly for low-income households, whose propensity to consume is higher;

- An incentive to consume rather than save.

Income support

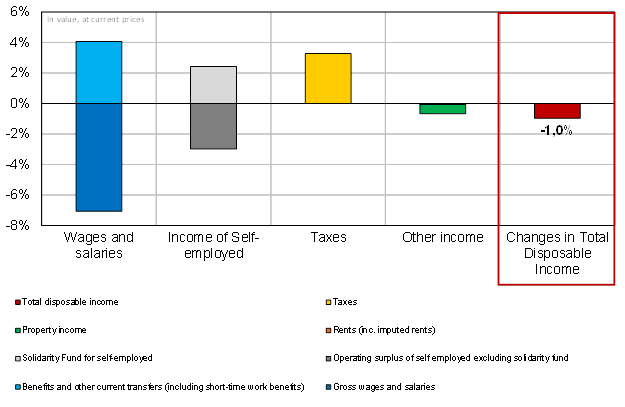

Figure 2, taken from the 2021 Economic, Social and Financial Report, details how households’ income was kept almost constant during the “great lockdown”. In particular, employees have benefited massively from the short-time work while individual entrepreneurs have been able to call on the solidarity fund.

Figure 2. Contributions to households’ disposable income growth in the second quarter 2020 (Year-on-year)

Sources : Insee (final results, T2 2020), DG Trésor

Over the whole of 2020, we expect households’ disposable income to remain stable on average, with a marked deterioration for households in self-employed or precarious jobs, which were the first affected by the jobs’ losses.

The recovery plan includes several mechanisms to support household income. First, the exceptional short-time work scheme will be extended for sectors subject to restrictions, while long-term partial activity agreements, which are currently taking off, will benefit to sectors hit hardly such as aeronautics. Secondly, the solidarity fund will continue to be accessible and will be extended to the very small businesses most affected by the crisis, their social and tax charges will also be reduced. Third, the back-to-school allowance, paid in August, has been increased by 100 euros to support low-income families, and scholarship students benefit from the 1 euro meal voucher.

Should the government do more? According to the latest data from the Banque de France (L’impact de la crise du Covid-19 sur la situation financière des ménages et des entreprises – août 2020), between March and August 2020, households’ cash holdings and bank savings increased by € 111 billion in total, while their bank borrowings increased by only € 25 billion. The additional net bank savings are therefore € 87 billion. Including life insurance, which suffered an outflow of € 7.8 billion over the period, net savings since March are close to € 80 billion.

According to an estimate made this summer by the OFCE, all income deciles experienced forced savings during lockdown, and the disposable income of the first two deciles remained stable overall. However, we can expect a sharp increase in inequality within these first two deciles. Supporting households hard hit by the crisis is an objective in itself, even if the transfers paid are not entirely consumed (some households, for example, may prefer to repay their debts).

Incentivizing consumption

The second way to stimulate consumption is to offer a temporary benefit such as a temporary VAT cut (Germany), subsidized restaurant meals (United Kingdom), or "eco-vouchers" (see, e.g., the proposal of MEDEF in June 2020). The idea is to temporarily encourage consumption, even if it means accepting a setback when the scheme expires. In the French recovery plan, the expansion of the already existing system Ma Prime Rénov’ follows this logic, in the area of investment (energy renovation).

The temporary VAT cut in Germany could boost consumption, provided retailers pass it on to their prices, which they seem to have done little so far (but it's a bit early to conclude). Across the Channel, the Eat Out to Help Out system allowed the British to dine in restaurants on weekdays by paying only half the bill for a month. Though the direct effect was an immediate 27% increase in consumption from Monday to Thursday, the measure also resulted in a drop in the number of weekend customers (-21%) according to the Center for Economic and Business Research.

In France, the experience of reduced rates (especially in restaurants) is not encouraging. Rather than being passed on to consumer prices, these VAT cuts have mostly benefited corporate markups (see Benzati and Carloni, 2019). While higher markups can help stimulate investment and employment, this goal is being pursued in France by lowering production taxes, which is a much more direct measure.

In Germany as in the United Kingdom, the measures implemented to stimulate consumption are costly because they are not targeted. Another option could be to distribute "eco-vouchers" or "green vouchers" with limited validity to low-income households, allowing them to buy goods and services from a restricted list of environmentally friendly consumption. Such a measure would simultaneously target three objectives: supporting the purchasing power of the poorest, reviving consumption and greening the economy.

In 2009, Belgium set up such an eco-voucher scheme distributed by companies to their employees using a model similar to holiday or restaurant vouchers. The green check takes the form of € 10 vouchers, capped at € 250 per year, which can only be spent on a list of goods labeled as durable. The logic is similar to some already existing French support schemes, such as support for thermal renovation or the purchase of electric bicycles.

The advantage of the green voucher over French aid is that it covers a wide range of products, which mitigates the risk of price increases. The downside is the complexity of implementation if you do not want to introduce distortions between products and between distribution channels. First, the list of eligible products must be defined, in cooperation with professionals and NGOs, and in accordance with European Union rules of level playing field (for example, it is impossible to favour local consumption or purely national labels). Then, retailers need help to adapt their labelling, checkouts and payment systems, all for a limited period since the measure is set to be temporary. The risk is a delay and significant implementation costs, and therefore an insufficient and late recovery.

Furthermore, a temporary scheme will have negligible impact on the environment. The different objectives come into conflict here. The purchasing power of poor households is better supported by means-tested transfers than by the distribution of green vouchers, especially if the latter are, like restaurant vouchers, intended for employees.

Beyond low-income households, relaunching consumption primarily involves reducing uncertainties: controlling the health situation, cushioning the negative effects of the crisis on employment. The main challenge is therefore the rapid deployment of the employment policies provided for in the recovery plan. Greening consumption is another objective that must addressed by specific policies and followed over the long term.

Read more :

>> Version française : Comment stimuler la consommation

>> All posts by Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, chief economist - French Treasury