Where does the money come from?

Post by Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, chief economist of the French Treasury.

If you are an economist like me, perhaps you were bombarded by questions from your relatives and friends during the summer break, around the theme:

Where does the money come from?

While the government seemed to be running out of money, trying to reduce the deficit, carrying out reforms in this direction; it suddenly takes a U-turn, pouring billions of euros to finance masks, tests, vaccines, but also companies whose revenues slumped during the health crisis, and households whose incomes would have otherwise collapsed. Our companies had no more customers, and yet we were still getting paid at the end of the month. How is this miracle possible? What’s the catch?

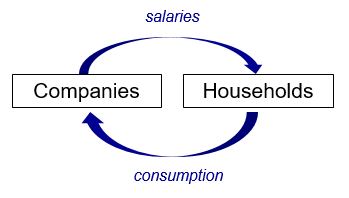

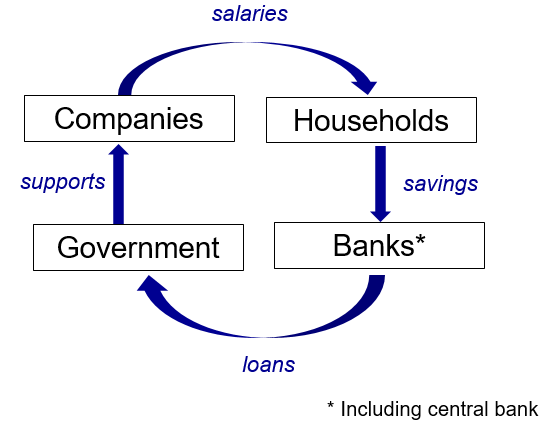

Everyone knows the normal money flow in the economy: firms pay their employees for their work; salaries provide the bulk of their income to households, which spend most of it on goods and services produced by firms, which pay their employees, and so on. (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The normal money flow in the economy

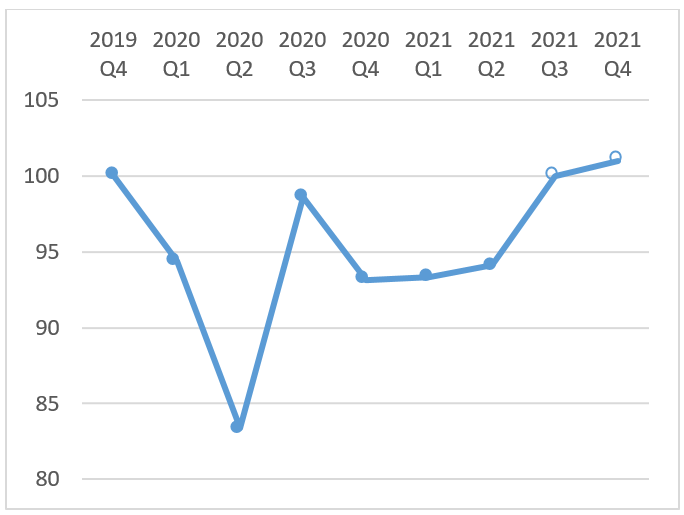

During the first lockdown, in March 2020, consumer spending fell sharply, unevenly across sectors; downstream sectors (such as restaurants) reduced their purchases of intermediate goods (such as bottles of wine), and the fall in sales spread through the economy (see Barrot, Grassi and Sauvagnat, 2020). I will illustrate the point here with the case of France, but the patterns are qualitatively similar in the other advanced economies.

Figure 2: Household consumption expenditure in volume

(Index 100 as of Q4 2019)

Source: Insee, Quarterly Accounts (30/07/2021) and Economic outlook (01/07/2021). Forecasts from Q3 2021.

Deprived of sales, many companies could no longer pay their employees, further damaging the circuit shown in graph 1. To avoid this catastrophic amplification of the economic crisis, the government very quickly put in place three types of support:

- Direct subsidies, notably through the solidarity fund and exemptions from social security contributions;

- A large extension of the short-time work scheme;

- State-guaranteed loans and deferral of contributions and tax payments.

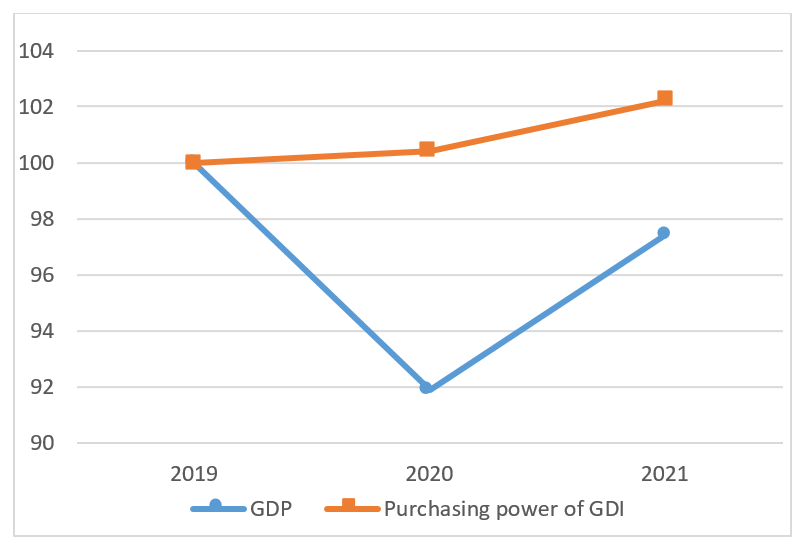

This support has enabled companies to continue paying salaries. The purchasing power of gross disposable income thus increased by an average of 0.4 percent in 2020, according to INSEE, while GDP fell by 7.9 percent (Figure 3).

Figure 3: GDP in volume and purchasing power of gross disposable income (GDI)

Index 100 in 2019

Source: Insee, Economic outlook July 1, 2021. Forecasts for 2021.

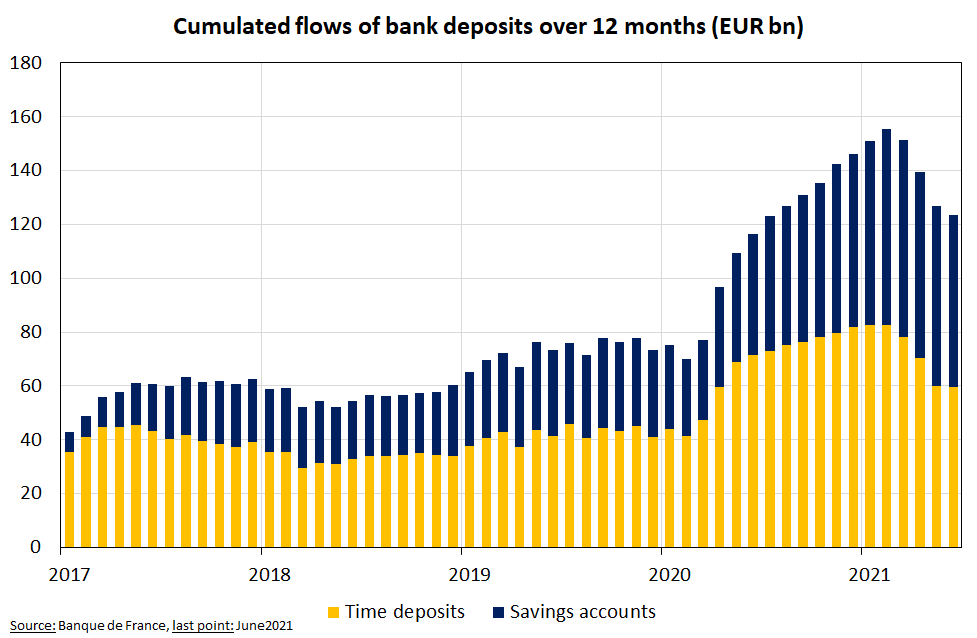

Thus, the purchasing power of households' gross disposable income increased in 2020 and 2021, but their consumption remained depressed on average over the period. Household savings therefore increased sharply. These savings were mainly hoarded in liquid form: bank deposits and saving accounts (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Net flows of liquid investments by French households

Households could have lent this money directly to the government, but this was complicated and not very profitable, since interest rates were (and still are) negative. Instead, they mainly left it in their bank accounts or saving accounts.

How did the banks invest your money? Broadly speaking, they had four choices:

- Keep the money as deposits in the banks' bank (the European Central Bank - ECB - via the Banque de France);

- Buy French public debt securities;

- Lend to French companies and households;

- Lend to foreign governments and companies.

The first two investments carried negative interest rates, but that was the price to pay to keep the money safe. The banks thus spread their assets over the four types of investments.

However, the ECB sought to encourage banks to lend more to the private sector. To do so, it offered to buy back their government debt, not only short-term securities, but also long-term bonds. In doing so, it wanted to encourage them to lend to other counterparts than the government, while putting downward pressure on the interest rates paid by all borrowers - public and private. In fine, the objective was to prevent the Eurozone from falling into a deflationary spiral: to facilitate public intervention, to encourage households to consume and companies to maintain their investment programs; in short, to sustain a certain level of demand despite the restrictions and uncertainties.

Together commercial banks and the central bank therefore recycled household savings to lend to the government, which in turn helped businesses to continue to pay out income to households: with the normal circuit of spending blocked, the government, with the help of the ECB, set up a temporary detour (see Figure 5). By keeping interest rates very low, the ECB has also reduced the cost of additional government debt, while encouraging firms and households not to cut spending too much.

Figure 5: The money flow in the Covid economy

Over the whole of 2020, French households saved around €100bn more than in 2019. They also invested less, so that their financial savings grew by around €110bn. For their part, public administrations financed €73.7bn of exceptional measures (including €27.4bn for short-time work, €15.9bn for the solidarity fund and €14bn in exceptional healthcare expenditure - amounts measured in national accounts). The government also guaranteed €130bn in bank loans to companies and granted them numerous deferrals of contributions (see details in the report of the Committe on the Monitoring and Evaluation of Financial Support Measures, July 2021). On the revenue side, the government has suffered from the fall in activity, which has reduced the various tax bases almost proportionally (although compulsory contributions have shown some resilience to the crisis, falling less than activity).

In accounting terms, the general government deficit in 2020 (€212bn in the provisional general government account for 2020) and the residual financing needs of French companies (€30bn) were largely financed by households (€180bn), via the financial system, with the remainder (€60bn) met by foreign investors. The money created by the banking system (primarily the ECB) does not change this accounting. Indeed, the bank deposits of households and companies are comparable to a debt of the banks towards them; and when you withdraw 20 euros from a cash dispenser, you only transform one form of asset (a bank deposit) into another (a banknote), without modifying the total. Thus, the banks have "borrowed" from households and businesses, as much as they have lent to them. The ECB's massive purchases of government debt have inflated its balance sheet in a balanced way on the assets and liabilities side. In other words, the ECB has created as many means of payment as it has acquired government debt.

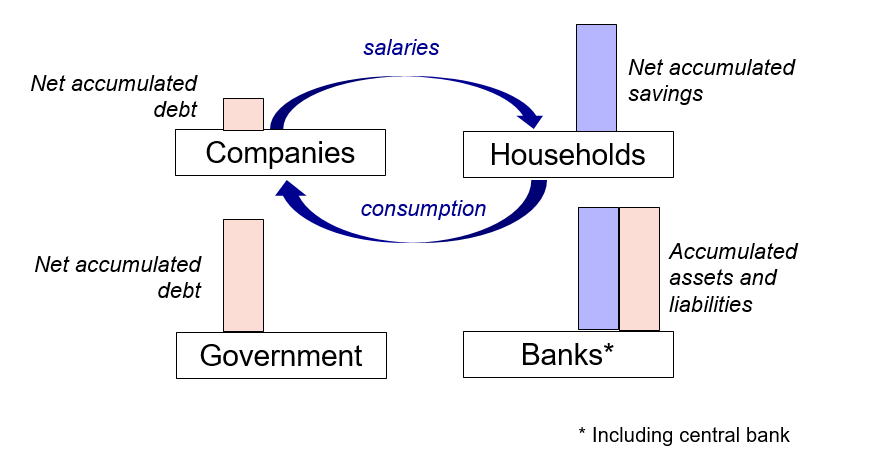

As the economy has reopened, households have returned to consumption and money has returned to its "normal" flow. However, everyone is coming out of the crisis with accumulated savings (households), accumulated debt (companies and especially the government), or both (commercial banks, ECB, see Figure 6). The key question will be how these stocks of assets and debts will influence the new flows of production and spending, and how they can gradually be deflated without stopping the recovery.

Figure 6: The money flow in the post-Covid economy

***

Read more :

>> Version française : D’où vient l’argent ?

>> All posts by Agnès Bénassy-Quéré, chief economist - French Treasury